It is spring in Washington, D.C., the air already hinting at the sticky summer humidity to come. Around the Congressional office buildings, aides scurry about in newly dusted-off seersucker. And in a crosswalk on Independence Avenue, Seattle's long-serving Democratic Congressman, Jim McDermott, is hurrying toward a vote on the floor of the House of Representatives.

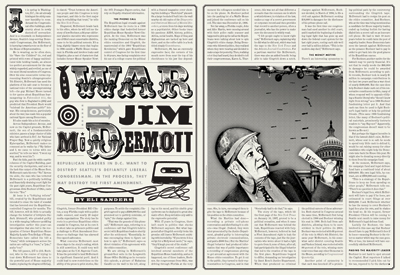

He is wearing, as he often does, his "Save the Children" tie, red and printed with rows of happy multicultural kids holding hands, an almost too-perfect accoutrement for the man widely regarded, and reviled, as one of the most liberal members of Congress. Over his nine consecutive terms representing Seattle's ultraprogressive 7th District, McDermott has used the platform of his safe seat to become a national voice of the uncompromising left—the guy Michael Moore turned to for quotes about Republican fear-mongering in Fahrenheit 9/11, the guy who flew to Baghdad in 2002 and predicted that President Bush would "mislead the American public" into war. His outspokenness, particularly about the war, has made him a popular national figure among Democrats.

It's also made him a lot of enemies.

Across Independence Avenue, and now on the Capitol grounds, McDermott, the son of a fundamentalist minister, passes a large cluster of kids who have arrived in D.C. for National Prayer Day. Now a quietly religious Episcopalian, McDermott makes no comment as he walks by. ("My father and I, we came to terms with one another," he tells me later. "I went my way, and he went his.")

Past the kids, past the white marble columns of the Capitol Building, past the security checkpoints, and now on the lush blue carpet of the House floor, McDermott casts his vote: "No." Across the aisle, the man who has tethered McDermott to a politically hobbling and financially draining court fight for the past eight years, Republican Congressman John Boehner of Ohio, casts his vote: "Yes."

At issue is a "lobbying reform" bill, created by the Republicans and intended to erase the taint of scandal that has hovered over the Republican-controlled Congress for months. The bill, however, will do little to actually change the behavior of lobbyists like Jack Abramoff, who pleaded guilty in a wide-ranging influence-peddling investigation earlier this year—an investigation that also led to the resignation of former Republican House Majority Leader Tom DeLay of Texas. Democrats have called the bill a "sham," while newspapers across the nation are calling it a "ruse," a "joke," and a "con."

The bill passes, 217 to 213. Boehner, who in the course of trying to tear down McDermott has risen to the powerful post of House majority leader, replacing the disgraced DeLay, is elated. "Trust between the American people and this Congress is very important, and this is the first major step in rebuilding that trust," he tells the New York Times.

Disgusted, McDermott heads back to his office, where he will tell me the story of how Boehner, a 56-year-old former plastics executive who represents one of Ohio's most conservative districts, came to be his political nemesis. It's a long, slightly bizarre story that begins in 1996 outside a Waffle House restaurant in Florida and involves leaks and litigation, plus a cast of characters that includes former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, former President Bill Clinton, a nosy Florida couple with a police radio scanner, and nearly 20 major media organizations. The story has its roots in a previous Republican ethics scandal in Congress, but at its core it is about take-no-prisoners politics and a challenge to First Amendment freedoms—a challenge that has alarmed free-speech advocates.

What concerns McDermott most these days is the story's ending, which is still unwritten. It could very well take place at the U.S. Supreme Court. It has the potential to land McDermott in significant financial peril. And it could lead to new restrictions on the ability of the press to print stories, like the 1971 Pentagon Papers series, that rely on illegally obtained information.

The Republican legal crusade against McDermott has its roots in a 1996 ethics charge that bedeviled former Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich. At the time, McDermott was the ranking Democrat on the House ethics committee and Gingrich, the mastermind of the 1994 "Republican Revolution," which gave Republicans control of Congress for the first time in 40 years, was facing complaints over his use of a college course for political purposes. To settle the complaint, Gingrich agreed to pay a $300,000 fine and promised not to publicly minimize, or "spin," the charge against him.

"That was the genesis of this phone call," McDermott says, referring to a conference call that Gingrich held in secret with Republican leaders shortly after the settlement. "Essentially, he was encouraging them to figure out how to spin it," McDermott says—a direct violation of his agreement with the ethics committee.

We are sitting in McDermott's ground-floor suite in the Longworth House Office Building as he recounts this episode, a picture of Mahatma Gandhi on the wall to his left, along with a framed magazine cover showing him holding a "Bush Lied" placard. On a large bookshelf built into the wall nearby sit old copies of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a totem from his days working as a psychiatrist. Other books trace his passions: AIDS, history, politics, Africa, social health. Maps of Iraq and Afghanistan are tacked up here and there, and on the coffee table is a book titled simply Guantánamo.

McDermott, 69, has an extremely expressive face; the corners of his mouth move from near the top of his cheekbones to his jaw line depending on his mood, and his nimble gray eyebrows can be deployed to great dramatic effect. Deep wrinkles only add to the expressive potential.

With 17 years in Congress, there isn't much in politics that shocks McDermott anymore. But what happened after Gingrich secretly broke his promise still leaves McDermott smirking with incredulity. "If you wrote it in a script for a Hollywood movie," he says, "they'd laugh you out of the studio."

Gingrich's secret conference call involved several members of the Republican House leadership, and as it happened, one of those leaders, Boehner, the congressman from Ohio, was driving through Florida at the very moment his colleagues needed him to be on the phone. So Boehner pulled into the parking lot of a Waffle House and joined the conference call on his cell. The date was December 21, 1996.

Not far away, a Florida couple, John and Alice Martin, were messing around with their police radio scanner and happened to pick up the call as the Republicans were talking about how to spin Gingrich's ethics charge. Being Democrats who followed politics, they realized whom they were hearing and decided to make a tape for posterity. Then, realizing what they had heard, they decided to tell their congresswoman, Karen L. Thurman. She, in turn, encouraged them to give the tape to McDermott because of his position on the ethics committee.

What the Martins had done—recording a private cell-phone conversation and distributing it to others—was illegal. (Indeed, they were later prosecuted by the Justice Department, pleaded guilty to intercepting private electronic communications, and paid a $500 fine.) But the Martins' illegal behavior had produced information that was of public importance: a recording of congressmen plotting to get around an agreement with the House ethics committee. To get it out to the public, they turned to their representatives in Congress, and in that sense, this was not all that different a scenario than the common one in which a whistleblower, in violation of the law, makes a copy of a secret government or corporate record and then provides that record to another person, often a journalist, who has the power to make sure the document is widely read.

"I felt people ought to know right now," McDermott says, explaining why he did what he did next, which was leak the tape to the New York Times and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. For a partisan warrior like McDermott, there was also an added benefit: being able to take Gingrich down a notch. "Somebody had to do that," he says.

The story of the tape, which hit the front page of the New York Times on January 10, 1997, proved to be a political sensation, and when it came out that McDermott was behind the leak, Republicans reacted with fury. McDermott, however, believed he had a First Amendment right to leak the contents of the tape, just like the journalists who wrote about it had a right to quote from it; none of them, after all, had participated in the illegal behavior that led to the creation of the tape in the first place. Republicans begged to differ, demanding an investigation by Janet Reno's Justice Department. When that produced no criminal charges against McDermott, Boehner decided, in March of 1998, to file a civil suit against McDermott seeking $10,000 in damages for the disclosure of his private phone call.

It was the first time one congressman had sued another in civil court, and it marked the beginning of a draining legal fight that has gone up and down the federal court system for the last eight years, costing each side well over half a million dollars. "This is the modern-day duel," McDermott says.

There's an interesting symmetry to the political careers of these adversaries. Both started in Congress around the same time, McDermott first being elected in 1988 and Boehner winning his seat in 1990. Both hail from safe districts, allowing them to be more strident in their politics (in 2004, Boehner was reelected with 69 percent of the vote in Ohio's 8th District; the same year McDermott, in his somewhat safer district covering Seattle and Vashon Island, was reelected with 80 percent of the vote, winning more total votes than any other Democrat in the House, according to Congressional Quarterly).

Another point of symmetry is that each was knocked off a promising political path by the controversy surrounding the Gingrich tape. McDermott had to resign his post on the ethics committee. And Boehner, who at the time was being mentioned as a candidate for House majority leader, ended up looking foolish for having dialed into a secret call on an insecure cell phone. He had to wait 10 more years before he could claim the post of majority leader. Some Democrats have seen the lawsuit against McDermott as the penance Boehner had to pay in order to get back into the good graces of the Republican caucus.

For Boehner, another motive for the lawsuit may be purely financial. It's not that he really needs the $60,000 in damages he could be awarded from McDermott; according to public records, Boehner took in nearly $1 million in campaign contributions in the last two years and has a war chest of nearly $400,000. But the case does help Boehner shake cash out of his conservative constituents in Ohio, many of whom respond well to appeals vilifying a Seattle liberal who "doesn't know right from wrong," as a 1998 Boehner fundraising letter put it. And that cash can then be used to fight Boehner's legal battle or help his political friends. (This same 1998 fundraising letter, like many of Boehner's political materials, prominently instructs readers to "say Bay-ner." Apparently, the congressman doesn't want to be known as Bo-ner.)

But perhaps the biggest incentive is that if the lawsuit didn't exist, McDermott, whose seat is so safe he needs to spend very little cash to defend it, would be out raising money for other candidates who might help the Democrats take back the House this year. He might also be donating money directly to them from his campaign fund.

At the moment, McDermott says, his campaign fund and legal defense fund have a combined total of about $490,000. His own legal bills, by contrast, are at $700,000 and counting.

"This is a strategy of the Republicans to keep me from spending on other people," McDermott tells me. "There's no question it does that."

Boehner's legal fees, which McDermott will have to pay if he loses, are estimated in court filings at over $600,000. I ask McDermott whether he has the money to cover Boehner's legal fees plus his own, and he shakes his head no. At his request, former President Clinton will be coming to Seattle next month to raise money for McDermott's legal defense fund.

Luckily for Boehner, the laws involved in this case say that Boehner doesn't have to pay McDermott's fees if he loses—meaning Boehner is the victor no matter which way the case goes. Win or lose, his lawsuit will have successfully sidelined McDermott.

Boehner is not hard to spot around the Capitol. Most reporters I talked to recommended I pick him out by his tan, reputed to be the darkest in the House, and their technique worked quite well. It proved impossible, however, to get the majority leader to comment on his motives in the suit against McDermott. His press aides told me he was too busy, and recommended I try his lawyer. In the Speaker's Lounge, an archetypal smoke-filled room off the House chamber where I'd heard I could send a page for any congressman, I was told that paging the majority leader is simply not done. I left cards at Boehner's offices, to no avail. Desperate, I went back to the veteran Capitol reporters for advice, and they recommended I try their stalking tactics, which basically involve buttonholing a reluctant congressman as he's leaving the chamber after a vote.

That afternoon, during a debate on homeland security, I sat in the press gallery above the chamber and zeroed in on Boehner, who is far more well-scrubbed than McDermott: sharp slate-gray suit, electric green tie, hair that reflects the House ceiling lights. He was hanging out near the back of the chamber, and as the debate ended I left the gallery, took up a position in the hallway beyond the chamber's back exits, and waited. And waited. The stalking trick, I discovered, depends on knowing exactly which of more than a dozen exits your subject is leaving from.

A photographer on the trail of some other politician consoled me, telling me that majority leaders take advantage of the maze of corridors and stairways leading from the House floor in order to avoid the press. "When it was DeLay he had a million ways to get in and out," the photographer told me. "He was like vapor."

But why would Boehner be trying to avoid talking about a case that he's relentlessly pursued for eight years? Isn't he proud of it?

His lawyer, Mike Carvin, later told me over the phone that Boehner is "quite proud of his efforts," and that when it comes to the question of why Boehner is pursuing the lawsuit, "the public record is quite fulsome with his explanations."

Essentially, Carvin says, Boehner believes that McDermott's First Amendment defense is "meritless" and that McDermott committed a crime by disclosing the contents of the tape, even if he wasn't personally involved in the original illegal interception. "People who knowingly violate the law to achieve the politics of personal destruction should have the statutes applied to them just like they would be to anyone else," Carvin says. "This case is about protecting people's private conversations over an important medium."

Democrats suggest a different reason for Boehner's current reluctance to speak publicly about the case. They say this is an inopportune time for the majority leader to be discussing a lawsuit that has roots in a Republican ethics scandal, one that also pits the majority leader against the First Amendment. As McDermott puts it, "They never thought this far down the road. They didn't think about what they were getting into."

One question that still dogs McDermott has to do with how he behaved at the beginning of the tape imbroglio. The Martins held a press conference shortly after the story broke and named McDermott as the recipient of their tape, but McDermott himself waited five years before admitting his role. In the meantime, he evaded questions and, in one case, lied. "I've never understood why he didn't tell the truth from the beginning," wrote Seattle Times columnist Danny Westneat in 2004, shortly after one of McDermott's legal setbacks in the case.

Looking back, it's certainly possible to damn McDermott as dishonest for not being more forthcoming about the tape at first. It's also possible to see him as having behaved like any anonymous source who unexpectedly gets outed—a bit unsteady and startled. McDermott explains his years of question dodging as a prudent response to the legal jeopardy he was facing.

Still, even as he was avoiding telling the truth, he says he discussed apologies and possible settlement figures with Boehner. The Republicans, he says, were never willing to accept anything less than an admission of guilt on the House floor. "They wanted me to go out and confess to a crime that I didn't believe was a crime, that I still don't believe was a crime," McDermott says. (For his part, Boehner's lawyer, Carvin, describes Boehner's settlement offers as "very generous.")

Seventeen media organizations have sided with McDermott, filing a brief in the lawsuit that argues that "a defect in the chain of title" (in this case, the Martins' illegal taping) should not make it illegal to publicize "truthful information on a matter of public importance." If sharing such information is illegal, media organizations and one conservative judge involved in the case have asked, then what's to stop Boehner from suing the papers that published the tape story? Or even the newspaper readers who later discussed the report with friends? (McDermott, by the way, likes to point out that Boehner hasn't sued anyone but him—proof, he says, that Boehner has singled him out for political retribution. Carvin replies that McDermott has been singled out because unlike the newspapers or their readers, he's a public official sworn to uphold the law, and unlike the Martins, he hasn't admitted any guilt.)

The list of organizations that have signed on to the brief includes the New York Times; the Washington Post; the Associated Press; CNN; Time Inc.; Dow Jones & Company, Inc. (publisher of the Wall Street Journal); Daily News, L.P. (publisher of the New York Daily News); and the Hearst Corporation (publisher of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer). "Those aren't my friends," says McDermott, pointing at the Journal and the Daily News. "These people are friends of the First Amendment."

Notably absent from the list: The Seattle Times, which in an April 9 editorial advised McDermott to give up the fight and accused him of "not acting ethically" in leaking the tape. "Doing this was in his political interest," the Times wrote. "Between the law and his interest, he chose his interest." The Times admitted that numerous other media organizations felt otherwise, but accused them, too, of pursuing their own interests.

Jill Mackie, the Times' spokeswoman, says managers at the paper can't recall if they were ever asked to support the brief. But the newsroom executives who would have been involved in that kind of decision, she says, would not have been influenced by the paper's editorial position.

Lucy Dalglish, who heads the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, another supporter of the brief, says the Times' editorial writers "are entitled to their opinion." But in her opinion, McDermott's position is important to defend. She points out that the story in the McDermott case broke the way two of last year's Pulitzer Prize–winning stories broke. The New York Times' report on the secret NSA domestic spying program and the Washington Post's exposé of secret CIA prisons in Europe both owe their existence to private information that was passed to reporters in violation of federal laws. McDermott is like those reporters, Dalglish says. He simply wanted to make important information public, regardless of its origin.

"If someone broke the law in obtaining the information, and you feel you need to prosecute someone, that's the offense that should be prosecuted, the actual offense," she says. "You should not penalize anyone for using important information once it's out there."

At the moment, the McDermott case is at the U.S. Court of Appeals in D.C., the last stop before the U.S. Supreme Court. He's surprised it has gone this far, given the Supreme Court's ruling in a similar 2001 case that, just like McDermott's, involved a damning audiotape that had been made by illegally intercepting a cell-phone conversation. That tape was passed on anonymously to a Pennsylvania radio station, which then broadcast the recording. In its ruling, a majority of the Supreme Court sided with the radio station, writing: "It would be quite remarkable to hold that speech by a law-abiding possessor of information can be suppressed in order to deter conduct by a non-law-abiding third party." The court then ordered McDermott's case to be reconsidered by lower courts in light of this ruling.

Lower courts, however, have disagreed, and are pushing McDermott's case back up the legal ladder—toward a Supreme Court that is now much different than it was in 2001. After a ruling against McDermott by a divided three-judge panel of the federal appeals court in March (with one of the more conservative judges dissenting because of First Amendment concerns), McDermott's lawyers asked the full nine-member appeals court to consider the case. That court is now deciding whether it will. If it decides not to, McDermott will appeal to the Supreme Court.

When the gavel bangs, McDermott takes up his inquisitorial posture, all of the warm openness erased from his face, replaced by a skeptical scowl. The Human Resources Subcommittee, part of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, is holding a hearing about unemployment insurance, and McDermott, the senior Democrat, is there to parry Republican attacks on the program.

A Republican tells the committee that many unemployed people aren't looking hard enough for new work. McDermott frowns, stares at the ceiling, and generally makes it obvious that he has a different perspective. An economist associated with the conservative Heritage Foundation suggests "radical freedom" should replace unemployment insurance. McDermott giggles, then laughs loudly enough for everyone in the room to hear. "This guy wants to get rid of [unemployment insurance] completely," he says, incredulous. "He thinks people would get back to work more quickly that way."

After the hearing, McDermott heads toward a meeting in the Capitol building. As we walk, he admits the lawsuit wears on him—like a chronic illness, he says. His posture is slightly stooped, no longer the upright ready-for-anything stance portrayed in old campaign posters in his office. The man who biked across Washington State in his first campaign for governor in 1972, and then, after losing that race, ran unsuccessfully for governor two more times, now tells me he doesn't bike much around Seattle anymore because his knees can't take the ascent back up to his home on Queen Anne Hill. But when McDermott gets to talking about the possibility that the lawsuit could boomerang against the very Republicans who have pushed it so hard, the fiestiness he showed in the hearing room returns and he loses any appearance of a man weakened by time.

"Who knows about this case today?" he asks, getting warmed up. "No one. It's buried." But if the fight ends up at the Supreme Court, he says, everyone will hear about it, and Republicans will have a hard time not being cast as villains who are trying to take away First Amendment freedoms.

Then, standing outside the reception room, his voice rising, McDermott asks rhetorically: Does Boehner really want this lawsuit, and its connection to past Republican scandals, to resurface right around this fall's midterm elections? Does Gingrich, who McDermott believes is considering a run for president, really want the Supreme Court to be taking up a case tied to his ethics flap just in time for the run-up to the 2008 presidential elections?

The Republicans and Boehner thought they were avenging Gingrich when they started this lawsuit, McDermott says, but a sword cuts both ways.

"You gotta be careful when you try to take vengeance. Because what goes around comes around."